|

1.

Estimates indicate that before 2050, racial and ethnic

minorities will be in the majority in the United States. It

therefore behooves universities to provide diverse role

models for an increasingly diverse population (Crichlow,

2017).

2.

Diversity is good for all students. They will be much

better prepared to face a multicultural world when exposed

to diverse individuals and perspectives in the classroom (Paloma,

2014, Cited in Crichlow, 2017).

3.

There are multiple benefits that accrue from increasing

number of professors of color. Among other reasons, such

faculty members play vital roles in the enrollment,

retention, achievement, and graduation of students of color.

Equally, it includes "the necessity for the full and

unfettered participation in American society, by all of its

members, if this nation is to survive economically,

socially, and spiritually.” (Daufin, 2001).

4.

It has been reported that the most persistent and

statistically significant predictor of enrollment and

graduation of Black graduate students is the presence of

Black faculty.

The obvious implications

are that an increase in the presence of Black faculty is

critical, but unless barriers are removed, conditions

improved, and concerted actions taken, the production of

Black faculty will continue to worsen (Daufin, 2001).

5.

The presence of Black academicians involved in research and

development is important for a number of reasons, but four

critical reasons are as follows: (a) to advance scholarship

in general, as well as to focus research on minorities and

the disadvantaged; (b) to provide necessary support for

Black and other minority colleagues; (c) to increase the

number of Black scholars in the field; and (d) through

research and development efforts, to have a significant

effect on policy and programs that may enhance students'

educational attainment and academic development (Daufin,

2001).

6.

Research has pointed out the essential roles of Black

faculty. Among others, it is pointed out that such faculty

value service-related activities (e.g., mentoring students).

They also are instrumental in graduating doctoral students

of color (Parsons et al, 2018).

7.

Advantages of African-American faculty at predominantly

White institutions include the importance of

African-American faculty in adding diversity to the teaching

faculty; the value of teaching courses from multiple

perspectives; the need to conduct research in a culturally

sensitive and appropriate manner; and, the importance of

serving as role models, mentors, and advocates for

African-American students (Phelps, 1995)

8.

The presence of Black faculty on campuses is inextricably

linked to the recruitment, enrollment, persistence,

retention, and graduation of Black students. Black faculty

serve as role-models and mentors, thereby helping to insure

the successful matriculation of Black students.

Unfortunately, Black professors are more likely at higher

risk for non-success in the tenure and promotion process, in

part, because of institutional racism and role expectations

demanded in many white colleges and universities (Spigner,

1990).

9.

The recruitment and retention of faculty members of color

in higher education is paramount to the future of our

nation’s colleges and universities (Stanley, 2007).

10.

The integration of diverse people into K-12 schools, the

workplace, and higher education helps address some of the

history and legacy of racism. Integration, however, is not

limited to the redress of past and present ills. Inclusion

benefits all students. Diversity will help American citizens

be prepared to compete in the multicultural settings of the

future (Garrison-Wade et al, 2012).

11.

The academy often fails to value the diversity of faculty

of color but the presence of diverse faculty provides added

value to institutions of higher education. Faculty of color

help promote the success of students of color in higher

education by providing much needed role models who can help

encourage loftier career goals and improved academic

performance. In addition, faculty of color offer diverse

perspectives to the academy’s knowledge base and research

focus (Garrison-Wade et al, 2012).

Over the past decade,

educational researchers including those cited here have

noted the positive influences that African-American

professors have on African-American students in PWIs, as

well as the positive social and academic effects that having

a diverse faculty has on all students. Despite these

positive effects and the fact that about 13 percent of the

US population is African American (United States Census

Bureau, 2013), in 2011, African-American faculty comprised

less than six percent of fulltime faculty members in US

higher education institutions (National Center for Education

Statistics, 2012). Moreover, African-American female

professors have been underrepresented more in PWIs than

African-American male professors (Jones et al, 2015).

Research indicates that retention rates are dismal because

of issues of isolation, marginalization, non-promotion,

among other reasons. If we are to take on white supremacy in

higher education in a meaningful way, we need to take

seriously these advantages of diversity and enact policies

and practices to bring them to fulfillment.

References

Burke, M. A., Smith, C.

W., & Mayorga-Gallo, S. (2017). The new principle-policy

gap: How diversity ideology subverts diversity initiatives.

Sociological Perspectives, 60(5), 889-911.

Crichlow, V. J. (2017).

The solitary criminologist: Constructing a narrative of

black identity and alienation in the academy. Race and

Justice, 7(2), 179-195.

Daufin, E. K. (2001).

Minority faculty job experience, expectations, and

satisfaction. Journalism & Mass Communication Educator,

56(1), 18-30.

Garrison-Wade, D. F.,

Diggs, G. A., Estrada, D., & Galindo, R. (2012). Lift every

voice and sing: Faculty of color face the challenges of the

tenure track. The Urban Review, 44(1), 90-112.

Jones, B., Hwang, E., &

Bustamante, R. M. (2015). African American female

professors’ strategies for successful attainment of tenure

and promotion at predominately White institutions: It can

happen. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice,

10(2), 133-151.

Murphy, R. (1988).

Social closure: The theory of monopolization and exclusion.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Parsons, E. R. C., Bulls,

D. L., Freeman, D. B., Butler, M. B. & Atwater, M. M.

(2018). General experiences + race + racism = work lives of

Black faculty in postsecondary science education.

Cultural Studies of Science Education, 13(2),

371-394.

Phelps, R. E. (1995).

What's in a number?: Implications for African American

female faculty at predominantly White colleges and

universities. Innovative Higher Education, 19(4),

255-268.

Spigner, C. (1990).

Health, race, and academia in America: Survival of the

fittest? International Quarterly of Community Health

Education, 11(1), 63-78.

Stanley, C. A. (2006).

Coloring the academic landscape: Faculty of color breaking

the silence in predominantly White colleges and

universities. American Educational Research Journal,

43(4), 701-736.

|

Segregation in Toledo Schools: The 20th

Century

By Lynne Hamer, Ph.D.

Part 2 of 2

Whereas Toledo schools

entered the 20th century officially

desegregated (see part 1 of this article), de

facto segregation and opposition to segregation

continued throughout the 20th century and

into the 21st. Historians who have

studied segregation in Toledo, namely Williams

(1977) and Musteric (1998) point to segregated

housing patterns as well as actions by the Board of

Education of Toledo Public Schools as the primary

reasons segregation continued, and archival

documents from TLCPL’s local history collection

support their observations. Knowing how segregation

has been perpetuated in the past, perhaps on purpose

and sometime simply out of habit, can help us in the

present to understand the effects of that segregated

schooling on our schools and community today.

Throughout most of the 19th

century, school attendance boundaries were based on

neighborhood boundaries—and still are, though the

rise in charter and private schooling has changed

that to some extent. Musteric (1998) documents that

in 1890, 75 percent of Toledo’s Black population

lived in four of eight wards; in other wards, Blacks

were “residentially concentrated on the fringes of

white neighborhoods” (Musteric, p. 9). |

|

Purposeful creation of

communities and neighborhoods within Toledo’s city limits

enhanced segregation: As documented in the local archives

and numerous local histories, in 1915, John Willys led

establishment of Village of Ottawa Hills within Toledo city

limits, and though it was not a separate municipality,

Westmoreland neighborhood was platted in 1918. Musteric

documented, “In 1917, efforts by blacks to move to the

Bulgarian and Birmingham neighborhoods of East Toledo were

met with threats and incidents. Two years later, 146 East

Toledoans filed a restrictive covenant agreement with county

officials, even though the Supreme Court had outlawed such

agreements.” Musteric concluded, “Toledoans were able to

limit their overt racial hostility, so long as their black

neighbors did not move outside of ‘black’ areas; when this

was attempted, white Toledoans erupted with open violence”

(1998, p. 12).

White violence, including

a particularly vicious attack on a Black family in East

Toledo (Musteric, 1998), or threats of violence maintained

strict segregation of housing through the 1920s, and

segregation of schooling resulted. The Board of Education

also acted to engineer segregation. Musteric (1998) told

how, “in 1920 the NAACP accused the TPS Superintendent

William B. Gitteau of ordering segregation of blacks in

certain public schools. At a school board meeting, NAACP

officials charged that Superintendent Gitteau had ordered

the segregation of blacks in the Industrial Heights School.

According to the allegations, all black students in the

school had been placed ‘under the charge of’ Miss Duffy, a

black teacher. Superintendent Gittaeu denied the charges and

said that it was the policy of the schools to ‘place all

backward pupils under one teacher.’ Members of the Board of

Education supported this contention and Board president W.

C. Carr added that board was not aware of ‘any segregation

other than this’” (p. 13).

With the Great Migration

in the 1930s, Toledo’s black population grew and housing

available for Black families became scarcer and poorer in

quality. Musteric describes “a distinct ghetto of 11, 000

blacks existed close to the downtown central business

district” (p. 10) as a result in part of restrictive

covenant agreements and in part simply a housing shortage

and poor-quality housing. Having migrated for railroad

work, some Black families ended up living in boxcars on

railroad sidings. The US Congress funded low income

housing, officially segregated with the designation of

“Negro houses” and “white houses”; in Toledo Black families

were mostly “in the Pinewood area, south of downtown Toledo”

(Musteric, p. 14).

The situation was

exacerbated by lack of employment opportunities and brutal

segregation tactics when employment was available. Musteric

reports that “in industrial work, blacks accounted for only

two percent of the total work force. Of those Blacks

employed, all were in semi-skilled or cleaning/janitorial

positions” while there were no active Black firemen and only

three or four Black policemen employed. By 1937, After four

years of New Deal, because of blatent and unapologetic

discrimination, Blacks were unemployed at 33 percent while

whites were unemployed at only 10 percent (Musteric, p. 15).

Parallel to segregation and discrimination in housing and

employment, the Toledo Board of Education also practiced

segregation, though always with an excuse that what looked

like racial segregation was actually due to some other

need. In 1937, TPS Superintendent E.L. Bowsher was charged

with segregating Black students by transferring Black

students from Washington Elementary to Gunckel Elementary;

he said that the transfer was due to Washington school being

overcrowded and Board backed this as reason for decision.

However, in 1938, two

schools were cited for overcrowding: Robinson and Gunckel.

This seemed to draw Bowsher’s 1937 stated intentions to

alleviate crowding into question, but the transfers stood (Musteric,

1998). During this time, Black teachers continued to be

assigned to Black schools, creating a segregated teaching

force and ensuring that white children were never under the

authority of Black adults. It was not until 1944, when

Emory Leverette was named assistant principal of Gunckel, by

then identified as the Black school, that TPS had any Black

administrators: Leverette was the first in TPS (Blade,

1998).

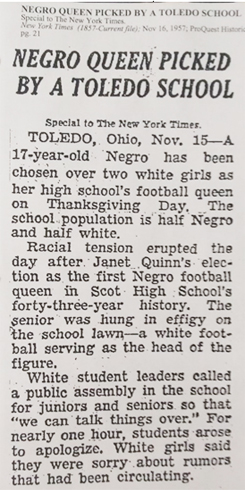

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme

Court ruled In Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka,

Kansas that “separate is inherently unequal” and proclaimed

state-sanctioned segregation of public schools violates 14th

Amendment. Some Toledo schools were already integrated, with

the population of Scott High School being approximately 50

percent Black ad 50 percent White. Musteric reports that

“when Scott High School crowned its first black homecoming

queen…, whites burned her in effigy” (p. 24). The New

York Times picked up the story as nationally significant

(see photo). (13 years later, when “Toledo University”

crowned its first Black homecoming queen, she was presented

with wilted flowers.)

Washington Township, which

had been incorporated in 1840 but had always been part of

the Toledo Public Schools, created their own Washington

Local Schools, thus creating a nearly entirely white student

body surrounded by an increasingly diverse Toledo public

schools (Messina, 2004).

The 1960s saw passage of

the US Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968, and Voting Rights

Act of 1965, and found Toledo experiencing suburbanization,

or white flight, leading to a more profound pattern of

racial segregation. In response to the changes at the

national scene, white “violence broke out in sections of the

city of Toledo. Looting was widespread and several cases of

arson.”

In the 1960s, TPS changed

from Gunckel being “the” Black elementary school to having

several predominantly black schools: Washington, Pickett,

Lincoln, Warren, Robinson, King, Stewart, and Fulton. While

in the spirit of the time a school board could have worked

on creating integrated schools, Musteric (1998) observes,

“The Toledo Board of Education did not deliberately

integrate its schools in the 1960s. Instead, the board

maintained segregated schools either by limiting the choices

of students, or …by making no effort to reverse the effects

of residential segregation, or both” (p. 23). Indeed, TPS

made affirmative decisions to maintain segregation in 1962

when the district opened Bowsher and Start high schools and

redrew existing school boundaries for all district high

schools except Scott: Scott High School was not involved in

redistricting and became the Black high school.

Students became leaders

demanding change. Musteric (1998) documents that in 1962,

Woodward High School students were suspended for protesting

about having “too few Negro teachers, no suitable history

course on Negro life, no Negro cheerleaders, and only a

token representative on the … athletic coaching staffs… At

Scott HS, 300 students who supported the demands by Woodward

students for a ‘Negro’ curriculum by boycotting classes were

suspended by black principal Flute Rice.”

They received response in

the form of the establishment of Woodward High School’s

“Negro History Week” (emphasis added), which was

immediately protested by the newly active white students’

group, United Citizens Council of America: “This is only the

beginning of more intolerable situations that will occur

unless we unite in a common cause for preservation of the

civil rights of white students” ” (Musteric, pp. 24-25).

Meanwhile, the TPS Board

of Education published their official position on school

integration on May 23, 1966: “The public schools will work

cooperatively with all community agencies in constructive

efforts to eliminate artificial separation on the basis of

race, religious, or economic conditions.” Despite these

intentions, a 1968 U.S. Department of Health, Education, and

Welfare study found TPS system non-compliant with civil

rights laws pertaining to integration of students and staff

in multiple areas (Musteric, 1998).

Musteric notes the insight

provided by Toledo’s local African-American newspaper, the

Bronze Raven, in a 1971 editorial, saying that it

perhaps best summarizes the impact of the 1960s upon the

schools: ‘During the last decade there has been some

improvement in integration in the Toledo Public Schools, but

no there are actually more schools that are predominantly

black than there were then [in the early 1960s]’” (Musteric,

p. 23).

In the 1970s, whites in Toledo increasingly sent their

children to private parochial schools, while the public

schools became increasingly overcrowded, with the

predominantly Black Pickett, Fulton, and Cherry schools most

seriously packed. Only two Black men had been on board of

education; only one Black administrator in a predominantly

white school; and while only one school did not have at

least one Black teacher, staff were lodging complaints

lodged with Ohio Civil Rights Commission about

discrimination (Musteric, p. 91-92).

In 1972 in Toledo, of 61 elementary and junior highs, “seven

had a black student enrollment of over 90 percent… Three

other schools had a black population of more than 80

percent…. 22 schools had no black enrollment” (Musteric, p.

87). In 1974, investigating TPS, the NAACP found “eleven

schools had all their black students in programs such as

special education, effectively creating a segregated ‘school

within a school’….” (Musteric, p. 87). Students and staff

were segregated by design, and acts of white violence

supported the design: the Bronze Raven reported many

incidents of violence and degradation against Black students

by the white teams and schools they played. When disruptions

occurred, it was the Black students who received punishment,

not the white (Musteric, p. 93).

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Swann vs.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, ruled that busing

could be used to achieve racial balance: both Blacks and

Whites opposed busing, but districts across the nation

experimented with it anyway—including TPS. But TPS made

what has been described as a half-hearted attempt at

integration using bussing.

Gregory Johnson recalls his experience “getting integrated”

when as an eighth grader, along with all his classmates and

four of their teachers, he was “shipped out” from Pickett

School to McTigue Junior High in the name of “integration”

(Johnson, 2009). Up until then, Pickett had been K-8.

Johnson describes having enjoyed school at Pickett, where

teachers practiced what we would now call reality

pedagogy (Emdin, 2016)—a pedagogy based in strong

relationships between teachers and students, the practice of

basing lessons in the real world, often through field trips,

and the belief that all students should be included.

At Byrnedale, it was all “the book,” and Johnson recalls

both the teachers and the students transplanted from Pickett

suffered culture shock—with many of the students also

suffering failure and being held back. When they did

graduate from eighth grade, Johnson recalls, the Black

students were “shipped back” to their choice of Scott or

Libbey high schools, while the white students, many of whom

had become their friends, were sent to Bowsher or Rogers.

Clearly, there was no intention of true integration with the

bussing experiment.

Johnson sums up: “I still don’t understand why we were

shipped out like that. The only reason I see why they

destroyed Pickett School like that was that the program was

going too well…. It doesn’t make any sense for them to have

shipped us out there and then shipped us right back…. The

only thing I can think of is ‘divide and conquer’” (2009).

The history of segregation continues to this day, with work

by Toledo’s African American Parents’ Association and others

challenging it and pushing us as a community toward

providing equitable, quality, antiracist education for all

students. This has been only a bit of the history, but

enough to provoke the questions: Why has Toledo Public

historically supported segregation? What has been the role

of “TU,” now the University of Toledo? How have segregation

and inequitable, racist practices affected us all, Black and

white, in creating and maintaining a racist society? What

are we doing about those effects and continued practices

now?

References

Johnson, G. (2009).

Getting integrated? A personal history of public schooling.

Pathways: The Literary and Art Journal of Owens Community

College. Rossford, Ohio.

Messina, I. (2004, Dec.

20). Washington Local, TPS Split Still Stirs Debate.

Retrieved from

https://www.toledoblade.com/local/education/2004/12/20/Washington-Local-TPS-split-still-spurs-debate/stories/200412200033

Musteric, M. (1998).

Perpetuating patterns of inequality: School segregation in

Toledo, Ohio in the 1970s. M.A. Thesis, BGSU.

Snyder, S. & Tavel, D

(1992). To learning’s fount: Jesup W. Scott High School,

1913-1988, the first seventy-five years. No place, no

date.

TLCPL Local History

archives.

Anti-Racism Teach-Ins: Understanding the Present through the

Past

Anti-Racism Teach-Ins: Critical Reflection for Change

Anti-Racism

Teach-Ins: Confronting Racism in Our Curricula

|