|

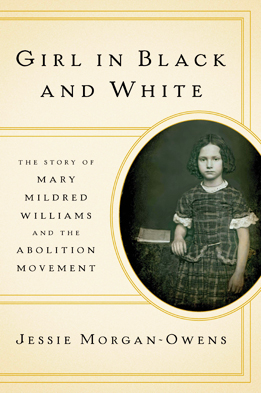

Girl in Black

and White

by Jessie Morgan-Owens

c.2019, W.W. Norton

$27.95 / $36.95 Canada

324 pages

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

The Truth Contributor

Water stains and tattered edges.

It was a shame that that happened to the picture you found,

though those wounds give it dignity. You have no idea who’s

in the snapshot; you just know that someone wanted to

remember a moment in time – or, as in the new book

Girl in Black and White by Jessie Morgan-Owens,

someone wanted to spark change.

If you didn’t know the whole story behind the daguerreotype,

you would think it was just an image of a charming,

anonymous little girl, circa 1855.

|

|

|

And you’d be half right.

Its story starts in 1808 when Virginia widow Conney Cornwell

dealt with a thorny issue: her 15-year-old daughter, Kitty,

became pregnant by one of Conney’s slaves and, ignoring

possible ruination of the family’s reputation, Conney kept

the baby they named John. Though he was technically free due

to matrilineal laws, John was raised in the slave quarters

by Conney’s slave, “Prue,” until he was 16.

In 1825, when Conney fell ill, she did something that she

hoped would ultimately protect Prue from enduring the

heartbreak of separation from family: Conney left Prue to

John in her will. Also included were Prue’s children and

future grandchildren – and there would be many, most

fathered by white men of power.

The problem was that John’s whereabouts were unknown when

Conney died, and there was a battle for her estate; in the

meantime, Prue gave birth to more children, as did her

children. Through complicated circumstances, one of them,

Prue’s very light-skinned granddaughter, eventually caught

the eye of anti-slavery Massachusetts Senator Charles

Sumner, who knew that white audiences would be interested in

her story and the horrors that might befall her as a black

child who looked white. He wanted to show her to his

abolitionist supporters and to opponents.

And so Sumner arranged a portrait session with a little girl

called Mary…

Much as you’ll be interested in Mary’s story, too,

Girl in Black and White may be a challenging way to get

it.

While it’s good that a major chunk of the first part of this

book is a Genesis-like account of begetting and ancestry,

that soon devolves into court cases and courtroom wranglings

that may be hard to follow for all but the most legal-minded

readers. Author Jessie Morgan-Owens valiantly offers some

help with this and she includes plenty of fascinating

side-stories on mid-1800s culture, photography, abolition,

and attitudes, but there’s still a lot to take in,

especially if you’re not prepared for it.

Take that as fair warning because, despite its depth, you’ll

have a hard time tearing yourself away from the small

stories Morgan-Owens offers inside the larger account: tales

of everyday life, helpful celebrities, and Mary’s final days

in what may have been a “’Boston Marriage.’”

Perhaps the best advice is to give yourself plenty of time

to digest and plenty of room to back-page while reading

Girl in Black and White. Do that, and you’ll be fine;

without space to contemplate, though, it may leave your

brain a little tattered.

|